- Odd-looking!

- Bizarre!

- Funny-faced!

- Strange!

- Weird!

These are some words that spring up when one sees a hammerhead shark for the first time. As one gets deeper into it, an incredible fascination builds up for the same odd/bizarre creatures!

Often considered one of the enigmatic wonders of the ocean world, the hammerhead sharks, with their uniquely shaped heads, are at the top of every marine researcher’s dream list, every diver’s wish list.

Possibly one among the most minor shark families, with two genera (Sphyrna and Eusphyra) and nine species, with the 10th one being discovered, instead uncovered, in 2013. The Sphyrna members are also known as Zygaena, Cestracion, and Sphyrichthys.

The earliest hammerhead species discovered was the Smooth Hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena) by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, while the latest member, the Carolina hammerhead (Sphyrna gilbert), was found and described in 2013.

Why the name?

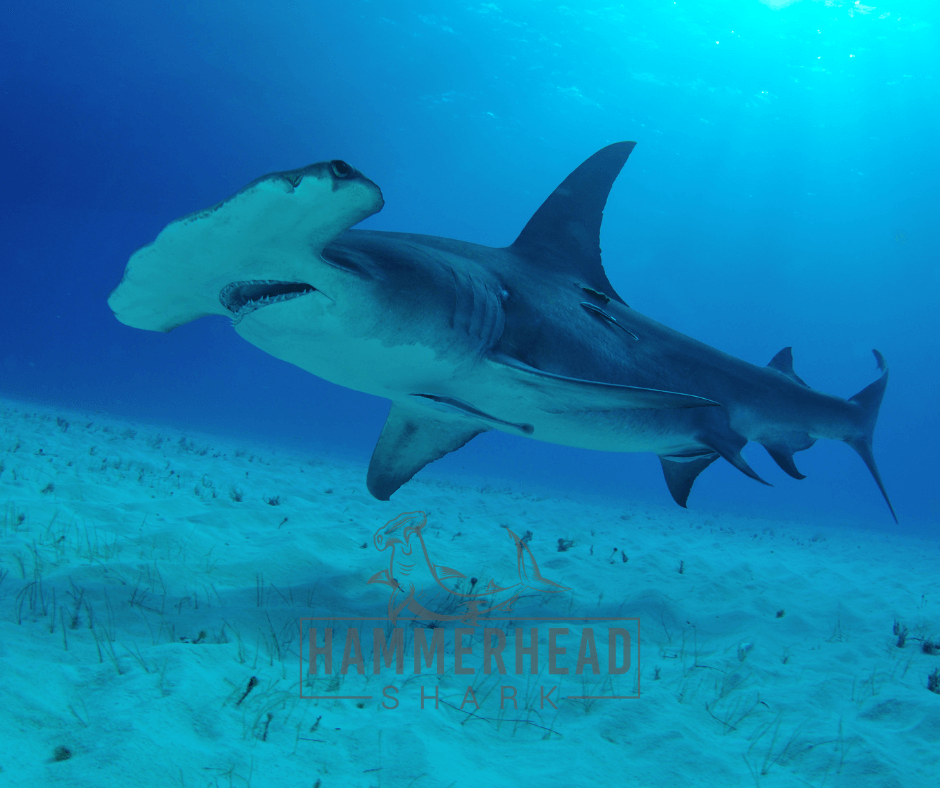

Perhaps the most easily identifiable of sharks belong to the family Sphyrnidae’s sole genus. Hammerhead sharks get their name Sphyrna from the Greek word, σφῦρα, which means ‘hammer’, from their laterally expanded, dorsal–ventrally compressed head, a most-recognized structure referred to as the cephalofoil.

Characterized by its hammer-shaped head, cephalofoil forms the strongly flattened front head with side extensions in the shape of an axe, mallet, or spade with eyes on the outer edges. Their distinctively shaped heads are used for sensory reception, manoeuvring, and manipulation of prey.

The cephalofoil has electro-sensory pores that allow them to locate electric signals emitted by potential prey – making them an aggressive hunter.

Eight-plus species

The hammerheads are the most easily recognizable of sharks, with a distinct lateral expansion on each side of the head.

The functions of this extraordinary headgear has been the topic of many assumptions, presuppositions and endless debates.

The hammerheads are close cousins of the whaler sharks of the family Carcharhinidae, in most respects, which includes many species known for their complicated social behaviour. The hammerheads are not to be beaten by their regular-headed kin in social sophistication.

Hammerhead sharks (Family Sphyrnidae) get their name from their laterally expanded, dorsal–ventrally compressed head; a structure referred to as the cephalofoil. Species within the family vary in head size and shape and body size in functionally significant ways.

With a set of massive teeth, their front and back teeth are blade-like with 1 point; their lower teeth are straight, and their upper teeth are oblique and deeply notched on the rear side.

Their teeth are unique and the only fossilized testimony to their existence, dating back to the Miocene Epoch, 20,000,000 years ago.

Binocular vision

With eyes on the end of its large lateral extensions of the cephalofoil, the ‘hammer’ head gives the shark superior binocular vision and depth perception.

Their eyes afford these sharks 360-degree vision in the vertical plane and allow them to see above and below at all times. That means the animals can see above and below them at all times, giving them the depth of visual field.

Slender bodies, varying in size

Within the family, various species vary in head size, shape, and body size in functionally essential ways.

Elongated with rounded bodies which are moderately slender, cylindrical or somewhat compressed, they usually sport a light grey with a greenish tint that transitions to white ventrally.

With five gill slits, the last one is over the front of their pectoral fins.

They have two dorsal fins behind the pelvic fins; the first is high, pointed with a short base, and the second is significantly smaller and comparable to the anal fin. The strongly asymmetrical crescent-shaped caudal fins with a notched base and a well-defined ventral lobe form the rest of it.

Location

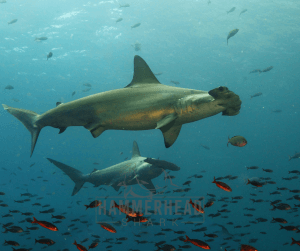

Known to be global travellers, the hammerheads are found in all tropical seas along coastlines and continental shelves. The Sphyrnidae Family, including the Bonnethead, the Hammerhead and the Scoophead Sharks and eight global members in one genus, Sphyrna, of which six species are found in Mexican waters, three in the Pacific Ocean and three in both the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean.

Nine species of hammerheads are found distributed across the warm waters of oceans of the world.

Found in the world’s warm oceans, they are seen near the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador, Malpelo Island in Colombia, near Molokai in Hawaii, Banda Island in Indonesia, Cocos Island off Costa Rica, and off southern and eastern Africa. According to National Geographic, though hammerheads are found in warm tropical waters, they participate in a mass migration to search for calmer waters in summer.

There are reports of hammerheads reaching the poles too in search of cooler climates, an example being the Smooth Hammerhead, known to enter the moderately warm seas in the summer and been observed even up to the shores of the Primor’e in Kaliningrad, Russia.

Eating habits

Among sharks, the hammerhead is known to be the best hunter. The credit goes to its uniquely shaped hammer-like head, which is said to have evolved, at least in part, to enhance the animal’s vision. The positioning of the eyes, mounted on the sides of the shark’s distinctive hammer head, allows 360° of sight in the vertical plane, meaning the animals can see above and below them at all times.

Thus, hammerheads which live in the coastal waters along the intertidal zone zero in on mainly benthic fishes and invertebrates. Their prey includes invertebrates, fish, rays, small crustaceans, and other benthic organisms which hide in the sands and sediment along these zones.

Sting ray is known to be a favourite!

Some hammerhead species are known to swim in schools during the day, sometimes in groups of over 100! But once the night falls, they become solitary hunters!

Hammerheads are also known to be vegetarians! Bonnetheads are known to feed on seagrass, which makes up as much as half their stomach contents. They may swallow it unintentionally, but they can partially digest it. This is the only known case of a potentially omnivorous species of shark.

Reproduction

Reproducing only once a year, it is initiated by the male shark, who bites the female shark violently until she agrees to mate. Females give birth to live young ones, exhibiting a viviparous mode of reproduction.

Like other sharks, fertilization is internal. The male transfers the sperm to the female through claspers, one of two intromittent organs. First, a yolk sac sustains the developing embryos. When the supply of yolk is finished, the depleted yolk sac becomes a mammalian placenta called a ‘yolk sac placenta’ or ‘pseudoplacenta’, through which the mother delivers nourishment until birth.

Once the baby sharks are born, they are on their own. They are not taken care of by the parents in any way. Usually, a litter consists of 12 to 15 pups, except for the Great Hammerhead, which gives birth to litters of 20 to 40 puppies. These baby sharks huddle together and swim toward warmer water until they are old enough and large enough to survive on their own.

An interesting fact is that in 2007, the Bonnethead Shark was found to be capable of asexual reproduction via automictic parthenogenesis, in which a female’s ovum fuses with a polar body to form a zygote without the need for a male. This was the first shark known to do this.

Dangers

Hammerheads are among the most threatened family of sharks, with more than half of the species on the verge of extinction. Living on or near continental shelves has mainly exposed them to extensive overfishing. Moreover, the depletion of mangrove forests has impacted their nursery habitat.

They are one of the most common victims of shark finning. Three more species have been placed on the ICUN Red List as critically endangered.

Human danger

Humans are most certainly known as the biggest threat to the hammerheads and many other creatures – great and small. Though not the primary target, hammerhead sharks are caught in fishing nets worldwide. Hammerheads are most commonly detected in tropical seas as they prefer to reside in warm waters.

The total number of hammerheads caught in fisheries is recorded in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Global Capture Production dataset. Sadly, the number increased steadily – from 75 metric tons in 1990 to 6,313 metric tons by 2010.

Shark fin traders say hammerheads have some of the best fin needles. Hong Kong is the world’s largest fin trade market and accounts for about 1.5% of the total annual amount of fins traded.

It is estimated that around 375,000 great hammerhead sharks are traded annually, equivalent to 21,000 metric tons of biomass. However, it is essential to note that most caught sharks are only used for their fins and discarded. The meat of hammerheads is generally unwanted, which, unfortunately, ends in their death.

Consumption of regular hammerhead meat has been recorded in countries such as Trinidad, Tobago, Eastern Venezuela, Kenya, and Japan.