Did you know that sharks pre-date dinosaurs? Shark ancestors first appeared over 450 million years ago before dinosaurs. Researches show that modern-day shark species, as we know it today, first showed up 370 million years ago.

Streamlined bodies, 5 – 7 gill slits, and large dorsal and pectoral fins characterized the sharks of then and today in classic shark appearance.

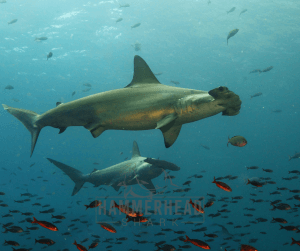

Around 20 million years ago, something unusual happened! In the evolution of sharks! Unlike the predators who have classic and streamlined bodies, the hammerhead shark arrived on the scene with a unique shape! With hammer-shaped heads.

A new study says that some 20 million years ago, the ancestor of today’s hammerhead sharks possibly first appeared in Earth’s oceans. Over time, they evolved into the various kinds of “strange-faced” fish – encompassing all shapes and sizes – that swim the seas today.

Sharks do not have mineralized bones and rarely fossilize. Hence, only their teeth are commonly found as fossils. Based on DNA studies and fossils, the ancestor of the hammerheads probably lived in the Early Miocene epoch about 20 million years ago.

Exhibiting wide, flattened heads, now known as cephalofoils, with bulging eyeballs at each end, hammerhead sharks easily the recognizable fish in the world!

These odd-faced creatures cruise warm waters around the world, from the Caribbean to Australia. They range from about 3 to 18 feet (1 to 5.5 meters).

Scientists on a mission to study the evolutionary history of hammerheads start with DNA. From eight species around the world, they have built a family “gene trees” dating to thousands to millions of generations and chronicling the split that led to new species! The hammerheads –from the original giant ancestor to smaller species.

Studies indicate that big hammerheads probably evolved into smaller hammerheads, and smaller hammerheads evolved independently twice, according to noted evolutionary biologist Andrew Martin of the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Researchers have found that the two ancestries of small sharks (3 to 4 feet in length) broke off from the main lineage, not once but at two different times during evolution. One species, the winghead shark, now lives in the warm waters north of Australia; the other, the bonnethead shark, inhabits the Caribbean and tropical eastern Pacific Ocean.

“Small is beautiful”

While reasons for evolution are being discussed and debated, “small is beautiful” is gaining traction.

The “incredible shrinking shark” over the ages may have been neoteny — the ability to achieve sexual maturity at earlier periods or the ability of adult sharks to retain juvenile traits. As the sharks became smaller, they may have begun investing more energy into reproductive activities instead of growth, says an evolutionary biologist.

However, smaller hammerheads don’t seem to get the same benefit as their bigger cousins. Cephalofoils provide “lift” to large hammerheads as they swim in the oceans like an aircraft wing. Smaller hammerheads don’t seem to get this same advantage, although they do get some other benefits.

It appears like prey detection and visualization get a better advantage than locomotion.

A significant advantage that the hammerheads get from larger cephalofoils is the sheer increase in the number of electrical sensors in their flattened noses and heads. It helps detect even extremely weak electrical emissions of the potential prey. Hammerheads can triangulate on their target, which is extraordinary.

Evolution mired in enigma

Sharks are known to be the apex predators in the ocean. Sharks first arrived on the scene over 450 million years ago, that is even before the dinosaurs! 370 million years ago, modern-day sharks first appeared. Sleek, streamlined bodies with 5-7 gill slits, and large dorsal and pectoral fins defined the modern-day sharks.

Just around 20 million years ago, a time pre-dating humans, an extraordinary episode happened in shark evolution. Defying the classic and streamlined shapes, the hammerhead shark arrived! With the most obvious, as what we know it today, the hammer-shaped head.

The hammer-shaped head, later called the ‘cephalofoil’, was learnt to be a highly evolved organ, putting the hammerheads high up the evolutionary chain. The large head actually amplifies the depth perception when compared to other sharks. In fact, of all the species of hammerheads, the winghead shark (which has the largest cephalofoil) has the best binocular depth perception

At one time, scientists concluded that the large cephalofoil acted like a plane’s wing and provided the lift. Later research shows it was not necessarily true. But, it does give greater manoeuvrability than most other sharks.

Most interestingly, the large cephalofoil provides the hammerheads with an uncanny sixth sense! The hammer-shaped head provides a greater area for the shark’s ampullae of lorenzini, the gel-filled pores on the snout that work like an electrical detector to find the tiny electrical signals made by all living things. This helps them target their prey, even hidden away in the sediments, and capture them with ease.

But, the answers to the question – why / how did hammerheads evolve as a separate genus – are evasive, and riddled with mystery. While there are bizarre reasons for the use their ‘cephalofoil’, those are not related to why it originally evolved. Nor are there any answers for why other sharks manage just fine without it.

Basically, the head provides extra lift and manoeuvrability, wider eye separation and greater area for sense organs such as smell and electric-field detection. In some species, it’s used to pin down struggling prey.

One thing is quite clear: unless something has evolved several times over, separately, it may be tough to state what selection pressures were involved. Fortunately, hammerhead species with very different head shapes and sizes exist.

Most recent study on DNA-based family trees of these eight species reveal a surprising element: species with astonishingly wide heads, like the Winghead shark (Eusphyra blochii), branched off first. That means the cephalofoil started as a huge organ before evolving into much smaller heads, like in Bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo).

This makes one thing abundantly clear: the hammer-head has tremendous sensory advantage – increased binocular vision or olfaction – rather than hydrodynamics.

That is the latest, under evolution, till date. The why and how of hammerhead evolution continues to elude mankind!