Hammerheads lead a fascinating life – beginning with their name! Which stems from their head! Which is in the shape of an unmistakable hammer!

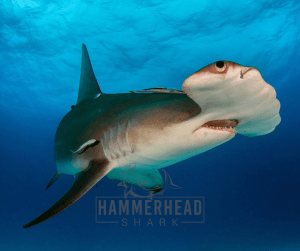

These sharks, from the family Sphyrnidae, have a distinctive hammer-shaped head called cephalofoil. The hammerhead shark’s cephalofoil serves many physiological purposes. It can help them navigate and find food, and it can also help them swim by boosting the hydrodynamic shape of their body.

1. Head as a hunting weapon!

The hammerhead is known to be an aggressive hunter. The credit goes to its uniquely shaped hammer-like head, which is said to have evolved, at least in part, to enhance the animal’s vision. The positioning of the eyes, mounted on the sides of the shark’s distinctive hammerhead, allows 360° of vision in the vertical plane, meaning the animals can see above and below them at all times.

There have been times that the hammerhead shark has been caught using its head to hammer down prey. They’ll use the blunt force of their heads to tire down prey, making them easier to eat.

2. Small Mouth

Hammerheads have a small mouths despite having a large heads, sometimes even more significant than their body. Unlike the horrors of movies like Jaws, hammerheads have disproportionately small mouths compared to other shark species.

3. Stingrays are its favorite snack!

Humans and stingrays are a pain to even put in one sentence. In addition to causing severe pain, fever, or swelling, they can also be fatal!

However, the deadly stingray is the No. 1 prey of choice for the hammerhead shark. Sting rays are most likely caught on the receiving end of this shark’s powerful hammering when hunting. To make a meal out of stingrays, the hammerhead shark is known to have evolved a tolerance to the lethal stings of the stingrays.

Reports suggest that one Great Hammerhead shark was photographed with the stingray’s barb still embedded in its skin.

4. Polar ahoy!

Primarily known to be inhabitants of warm oceans, hammerheads are known to migrate towards calmer waters, sometimes as far as the poles!

5. Critically endangered

Sadly, the entire Sphyrnidae family, which includes 9+1 species, is endangered, five of which are critically endangered.

Only the Carolina hammerhead shark (Sphyrna gilberti) does not figure in the endangered list because not enough data has been collected about this rare shark, the newest species to be discovered.

6. Not fossilized evidence

Sharks do not have mineralized bones and, thereby, rarely fossilize. Only their strong teeth are found as fossils, leaving little trace of the early hammerheads. The closest known ancestor of the hammerheads perhaps lived in the Early Miocene epoch about 20 million years ago.

7. Hammerhead sharks are shy

Can you believe that these aggressive hunters of the water world are pretty timid? By and large, they avoid human encounters. To help them feel comfortable in human company, researchers swimming with hammerhead sharks have one rule: no exhaling bubbles when they’re nearby! Lest they are frightened and scurry away!

8. Blind spot in binocular vision

Hammerheads are known to have binocular vision, thanks to their eyes mounted on the extreme edges of the hammer, the cephalofoil. They have a complete 360-degree range of vision – everything below them and above them is visible. But in front of them? Not so well. The exact positioning of their eyes leads them to have a blind spot right in front of their nose!

Besides this minor setback, the hammerhead shark has excellent eyesight and better depth perception than its shark cousins.

9. Cannibalism

Apart from being the most aggressive of hammerheads, the Great Hammerhead shark is known to eat other hammerheads; sometimes, it’s it’s own young.

10. Dinosaur peers

Sharks are known as prehistoric hunters who have been around since the time of dinosaurs. They are traced back to at least 420 million years ago.

But, the hammerhead sharks have not been around that long. Researchers say the evolution of the hammerhead shark began around 20 million years ago. Which still pre-dates humans!

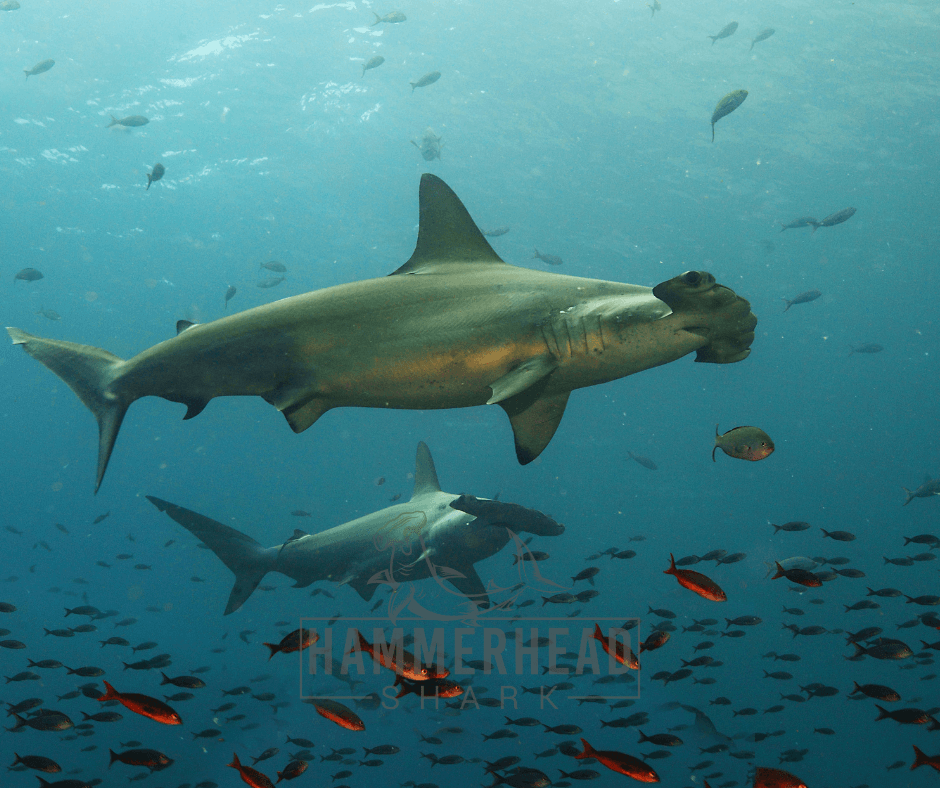

11. Hammerheads mostly swim sideways

In addition to the unique hammer-shaped head, the hammerhead shark also has fins of different lengths compared to other sharks. This influences the way they swim.

The slight swimming angle is unmistakable if you see a hammerhead shark swimming in the wild. This is because their first dorsal fin is longer than their pectoral fin, which is needed to swim competently. By tilting, hammerheads can use their dorsal fin in their small pectoral fin’s place. This gives a slight twist to their swimming, looking like they are swimming sideways!

12. Widest head

Compared to its body, its head, the cephalofoil, is almost half as wide as its body is long! Their sheer size, so vast, is known to be one of the reasons they get caught in fishing nets.

13. Cloning?

Cloning may not necessarily be the right word, but Bonnethead is known to undergo parthenogenesis. What would this mean is that a female shark was able to create offspring, all by herself, by fertilizing her eggs!

This extremely-unusual phenomenon was recorded in a Bonnethead shark.

14. Hammerheads are not a danger to humans

Contrary to the widespread fear, not a single human casualty has been reported in the only 17 unprovoked attacks reported on humans by hammerhead sharks since 1580, according to the International Shark Attack File.

Scalloped Hammerheads get tans!

While it is known that sharks get cancer, researches show that young Scalloped Hammerheads appear to acquire cancer-free suntans! When young Scalloped Hammerheads were kept in shallow outdoor pools, their skin darkened, going from a light beige to a rich chocolate brown!

This exceptional discovery was further studied. Researchers said that the experiments demonstrated that the “sharks were truly sun-tanning and that the response was, in fact, induced by the increase in solar radiation”.

The melanin content was recorded to have increased by 14 per cent over 21 days, and up to 28 per cent over 215 days.

”Despite all the tanning they’d done, there wasn’t a trace of skin cancer on any of the test sharks,” added a press release from the researchers.